How mortgage fees affect rates and spreads

Blog post

February 7, 2019

How could potential changes in U.S. mortgage policy and possible long-term industry trends affect mortgage-related fees and rate spreads? We find that recent developments could lead to lower fees, as well as compress rate spreads by roughly 45 basis points (bps). These long-term changes could in turn influence the direction and level of the primary mortgage rate, substantially impact prepayment risk in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and create hedging challenges for holders of MBS. Investors may benefit from considering how changes in the level of mortgage-related fees could influence rates and spreads.

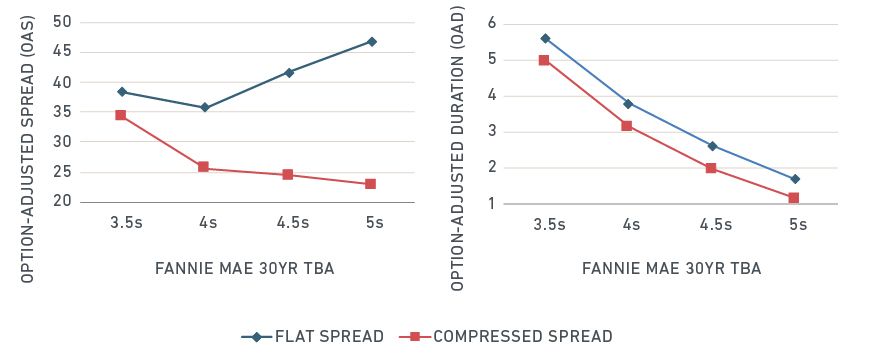

Different assumptions for mortgage-rate spreads lead to drastic valuation and hedging differentials

Source: MSCI

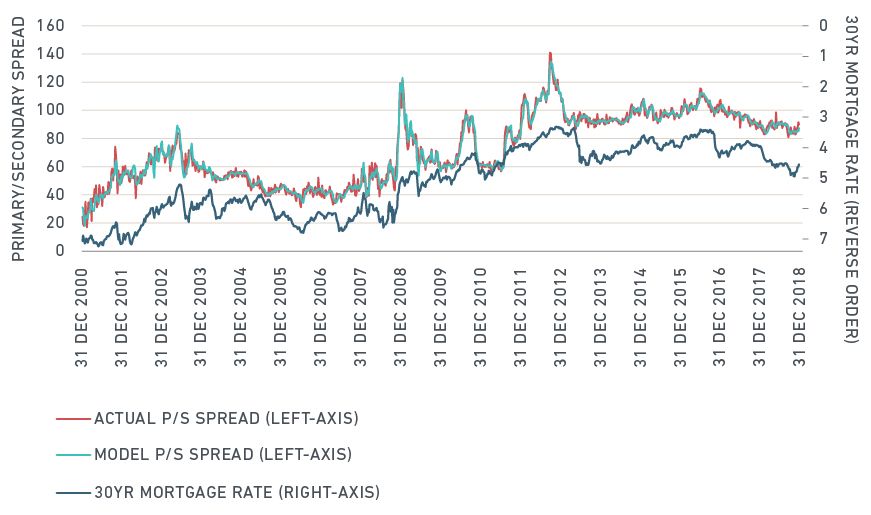

The primary/secondary (P/S) mortgage-rate spread — the difference between the primary mortgage rate and the current coupon yield of secondary to-be-announced (TBA) MBS1 — widened from approximately 45 bps before the crisis to roughly 100 bps in 2014 and 2015, but has since compressed to around 80 bps. MSCI's mortgage-rate model2 aims to capture this complexity by taking into account both short-term movements and long-term trends, including the minimal spread widening that took place amid the recent 48-bp rally in the benchmark 30-year fixed-rate mortgage.3 Let's inspect the trends driving the P/S spread's two components: the government-sponsored enterprises' guarantee fee (g-fee) and the origination fee.

High volatility in historical P/S spreads

Source: Freddie Mac, MSCI

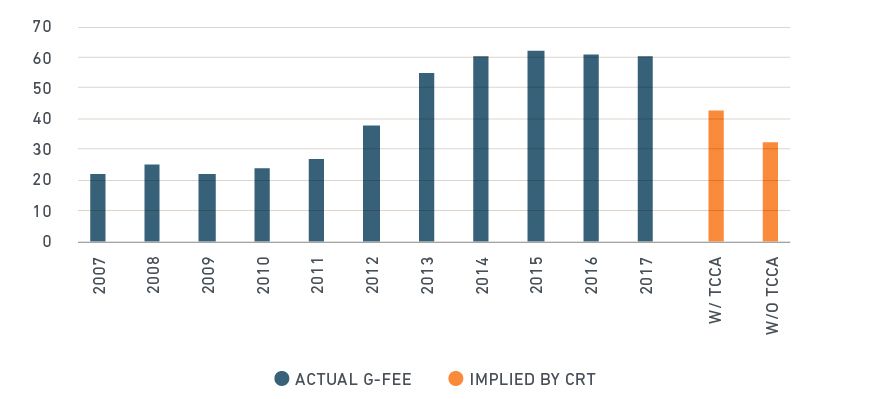

Potential g-fee compression

The g-fee, which has increased from below 25 bps before the crisis to above 60 bps in recent years, consists of two parts:

- Non-credit cost: Currently at 25 bps, it covers general administrative fees, non-transferrable operational-risk expense and a 10-bp allocation to the Treasury under the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011 (TCCA). The TCCA's scheduled expiration in 2021 could reduce the P/S spread by 10 bps.

- Credit cost: Currently around 36 bps, it is the price at which the GSEs sell credit-risk protection. This covers potential loss incurred by expected future borrower default, as well as the cost to hold the capital required to offset unexpected losses. Since 2013, the GSEs have bought this protection via credit-risk transfers (CRT), taking advantage of the large purchase-sale spread to deliver more than $100 billion in profits to the Treasury.4 If the GSEs and Treasury decide to pass this benefit on to homeowners, we calculate that the g-fee could compress by 18 bps, to be consistent with the level of the mortgage credit risk priced in by capital markets.5

28-bp g-fee compression?

Source: FHFA, MSCI

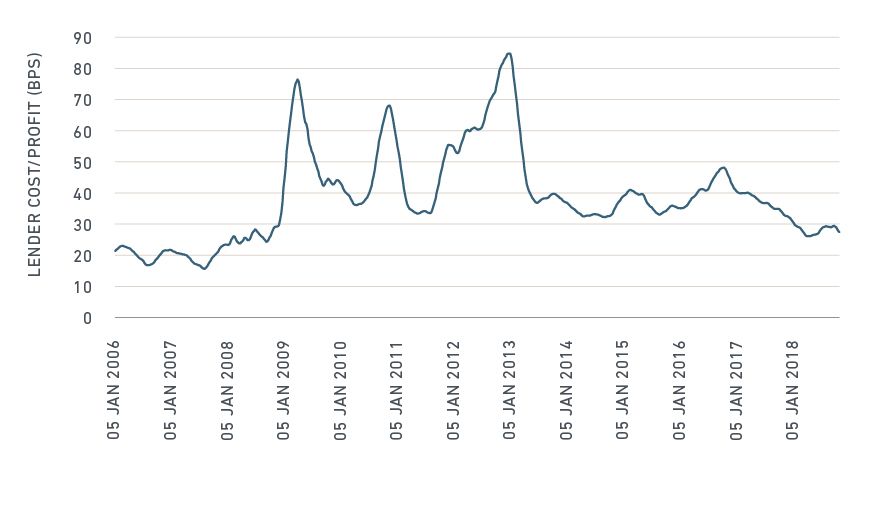

Potential origination-fee compression

Origination fees averaged around 20 bps before the financial crisis. Large refinancing volumes triggered by the Federal Reserve's quantitative-easing programs increased lenders' pricing power over borrowers, which increased origination fees to as high as 80 bps. Rising rates, however, have led to decreased origination fees, as lenders compete for decreasing loan demand. Currently at 30 bps, can origination fees go even lower — to the pre-crisis level of 20 bps or below?

Origination fees, driven by refinancing volumes, may decrease further

Source: FHFA, MSCI

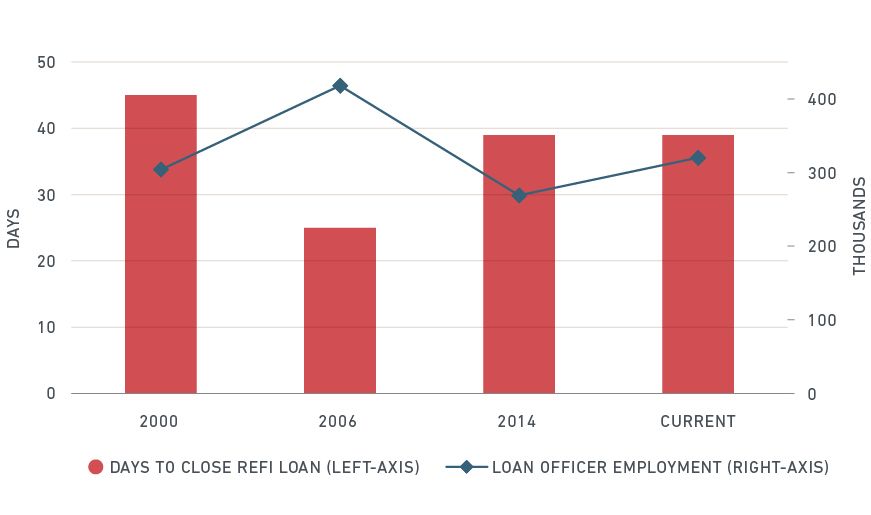

We have identified time periods with similar prepayment intensity (i.e., years with conditional prepayment rates of roughly 10%) and compared loan-officer employment with the average number of days to close refinancing loans. Current loan-officer employment is somewhat low by historical standards, despite post-Dodd-Frank-Act underwriting regulations. In pre-crisis 2006, there were more loan officers employed (418,000 vs. 320,000 today), and loans took fewer days to close (25 days on average vs. 39 days currently). Numerous technology vendors and non-bank mortgage originators have driven higher industry efficiency, among other reasons for this trend.7, 8

Loan-officer employment and closing times in periods with 10% CPR

Source: Federal Reserve, HMDA, Ellie Mae, MSCI

Putback risk can contribute around 5 bps to the current cost.8 GSE programs, such as Day 1 Certainty,9 aim to digitize the underwriting process (property-appraisal waiver, automated income verification, etc.) — an effort that may make loan origination more efficient and reduce putback risk. Also, mortgage underwriters in the years since the crisis have been held to much tighter standards than those in the pre-crisis era — further reducing putback risk.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency's upcoming launch of uniform MBS (UMBS)10 will likely accelerate the GSEs' efforts to fully digitize the mortgage process. A 20-day reduction could result in cost savings of $3,240, according to one industry estimate.11

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) lowered the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. The temporary profit boost will likely diminish over time due to competition. Based on our analysis, the new equilibrium level of lender cost/profit could drop by 7 bps.12

The origination fee could potentially revert from the current 30 bps to the historical 20 bps, due to lower origination cost and putback risks. With an additional 7-bp tax benefit, the origination fee could compress by 17 bps in total.

In sum, P/S spreads might compress by roughly 45 bps, driven by potentially lower G-fees (28 bps) and origination fees (17 bps), although the timing and amplitude of this spread compression remain uncertain. These potential long-term changes could have significant implications for MBS investors.

Further Reading

Subscribe todayto have insights delivered to your inbox.

1 Zhang, D. (2017). “MSCI Agency MBS Current Coupon Marking Model.” MSCI Model Insight. Client access only.2 Yu, Y. (2018). “MSCI Primary/Secondary Mortgage Spread Model.” MSCI Model Insight. Client access only.3 Freddie Mac. “Primary Mortgage Market Survey.” Data retrieved on Jan. 31, 2019.4 Fannie Mae. (2017). “Year-End Results/Annual Report.” Freddie Mac. (2017). “Annual Report.”5 Federal Housing Finance Agency. (2018). “Credit Risk Transfer Progress Report.”6 Ellie Mae. (2018). “Ellie Mae's True Digital Mortgage Reduces Application Close Time by Three Days.”7 “The New Mortgage Kings: They’re Not Banks.” The Wall Street Journal. Sept. 6, 2018.8 We assume 15% probability of a very adverse market environment, with 10% cumulative default; 50% of severity; 50% of putback probability; and 50% success rate of GSE putback effort.9 Fannie Mae. “Day 1 Certainty.”10 Federal Housing Finance Agency. (2018). “FHFA Announces June 2019 Implementation of the New Uniform Mortgage-Backed Security.”11 Mortgage Bankers Association. (2017). “MBA Annual marks the anniversary of Day 1 Certainty. Fannie Mae’s Andrew Bon Salle shares thoughts.”12 We define after-tax ROE as: revenue x profit margin x (1 - tax rate) / equity. We assume that the most conservative hedging/funding with TBA and revenue approximately equals the P/S spread + upfront origination fee (including non-lender fees, such as for title insurance). We assume that, with the same after-tax ROE before/after the TCJA, we can estimate the new P/S spread and upfront origination fee to be roughly 5 and 2 bps lower.

The content of this page is for informational purposes only and is intended for institutional professionals with the analytical resources and tools necessary to interpret any performance information. Nothing herein is intended to recommend any product, tool or service. For all references to laws, rules or regulations, please note that the information is provided “as is” and does not constitute legal advice or any binding interpretation. Any approach to comply with regulatory or policy initiatives should be discussed with your own legal counsel and/or the relevant competent authority, as needed.