Diversifying Away Cash Drag

Key findings

- Constructing self-financing private-capital portfolios, where distributions exceed contributions, can simplify a limited partner’s liquidity-management strategy and reduce cash drag.

- Predictably, increasing the number of commitments within an asset class or strategy reduces the uncertainty — or dispersion — of net cash flows each quarter but does little to smooth cash flows over time.

- Diversifying across asset classes can reduce downside cash-flow volatility relative to most types of asset-class-specific portfolios, thereby also reducing the precautionary liquidity required to meet capital calls.

Cash drag — the opportunity cost of holding low-return liquid assets to meet potential capital calls — is a common complaint among private-capital investors. The uncertain timing and magnitude of cash flows force limited partners (LPs) to maintain precautionary liquidity — cash on hand to meet net capital calls — in excess of expected capital calls because realized capital calls may ultimately be greater. In this blog post, we explore how diversifying a portfolio can reduce cash-flow risk and thus cash drag.

Positively correlated cash flows tend to occur at the same time and in the same direction, leading to lumpy inflows and outflows as well as an increase in volatility from quarter to quarter. In contrast, uncorrelated cash flows are less likely to coincide, creating smoother, more predictable cash flows over time. While smooth expected cash flows are attractive, LPs need to worry about how accurately they can predict cash flows. For instance, it is useful to know that the expected net distribution is USD 100, but it is critical to be aware of whether there is a 10% chance that you could actually face a USD 20 net capital call.

To determine the likelihood of any potential cash flows, we take an approach similar to the one used for value-at-risk models.[1] We simulate realistic portfolios of funds that are randomly sampled from the Burgiss Manager Universe (BMU) to demonstrate the importance of diversification in ensuring predictable and manageable cash flows.

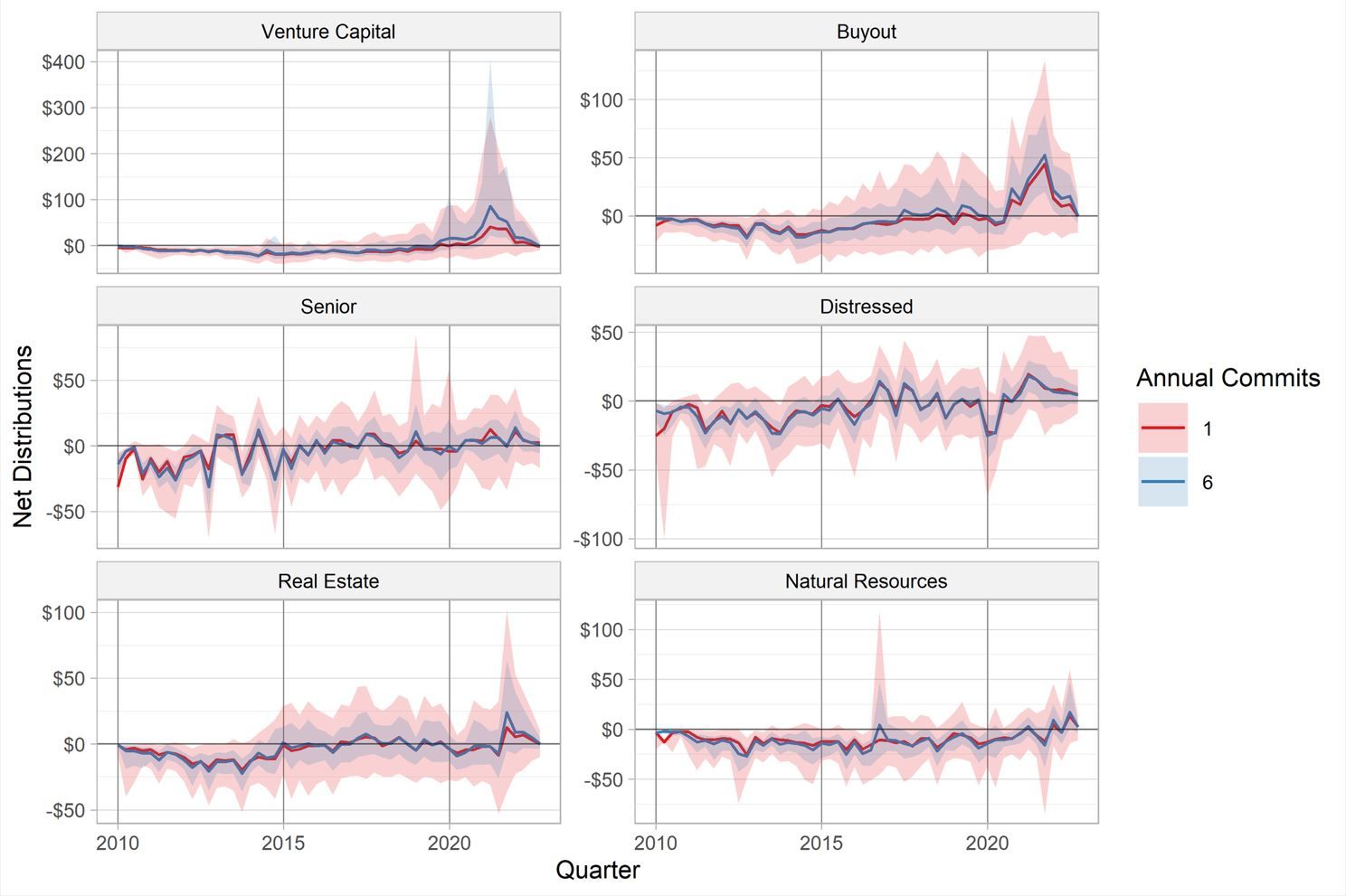

Diversifying within an asset class

We replicate an LP committing USD 100 to each vintage of an asset class by randomly sampling funds from the BMU to create a probability distribution of cash flows.[2] The exhibit below provides a simple demonstration of the power of diversification within portfolios beginning in 2010. We simulate the net cash flows from two different types of portfolios per asset class; one portfolio allocates USD 100 for each vintage to one fund and the other portfolio evenly splits the USD 100 across six funds. Predictably, increasing the number of funds has little impact on the median cash flow, but it substantially reduces the dispersion of possible cash flows within a given quarter. Adding more commitments diversifies away each fund's idiosyncratic cash-flow risk.[3] However, cash flows remain volatile from quarter to quarter.[4] While there are obvious benefits to diversifying commitments within an asset class, this approach is unlikely to produce a self-financing portfolio.

More fund commitments in an asset class, but limited diversification

Quarterly cash flows from simulated asset-class portfolios with different numbers of commitments per vintage. Commitments begin with the 2010 vintage. The lines denote the medians of each portfolio, and the ribbons indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles of the simulated portfolios.

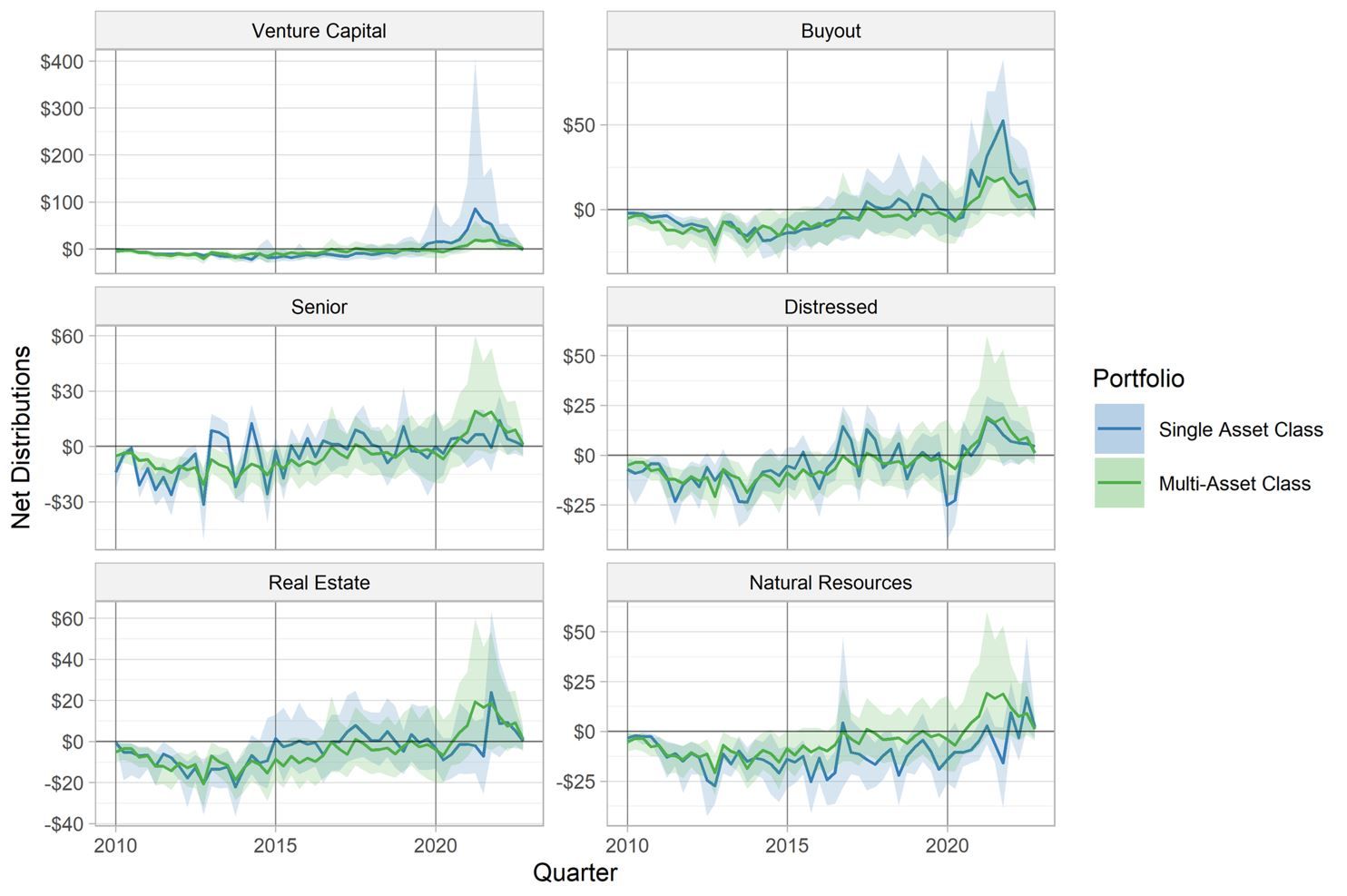

Diversifying across asset classes

While we are able to diversify away some idiosyncratic and temporal cash-flow risk by committing across six funds of the same asset class per vintage, we could reasonably expect to diversify away additional cash-flow risk by committing across asset classes. Intuitively, one would expect cash flows from two funds in different asset classes to be less correlated than the cash flows from two funds in the same asset class; if this is true, we should expect to see less net capital-call risk in the multi-asset-class portfolio than in the single asset class portfolios, as indicated in the exhibit below by the portions of the shaded ribbons below the median. The exhibit below compares the annual six-commitment portfolios from the exhibit above with our new asset-class-diversified portfolio. The asset-class-diversified portfolio is analogous to the six-commitment portfolios, except its USD 100 commitments per vintage are evenly allocated to one fund from each of the six asset classes in question.[5] Because both types of portfolios in the exhibit below commit to six funds per vintage, they are comparable in idiosyncratic and temporal diversification.

For debt and real assets, it is clear that diversifying across asset classes reduces downside cash-flow risks; the single-asset-class portfolios exhibit occasional large net capital calls, while the multi-asset-class portfolios have more predictable capital-call risk. However, this effect is much less obvious than in the comparison between asset-class-specific portfolios with one annual commitment and those with six annual commitments. The addition of asset-class diversification appears to smooth cash flows over time, making the multi-asset-class portfolio's net cash flows less volatile than those of the individual-asset-class portfolios.

Lower capital-call risk through diversifying across asset classes

Quarterly cash flows from simulated asset-class portfolios committing to six funds per vintage, compared to cash flows from simulated portfolios that invest equally in one fund from each of these six asset classes per vintage. Commitments begin with the 2010 vintage. The lines denote the medians of each portfolio, and the ribbons indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles of the simulated portfolios. The multi-asset-class portfolio (green) is the same across all six panels.

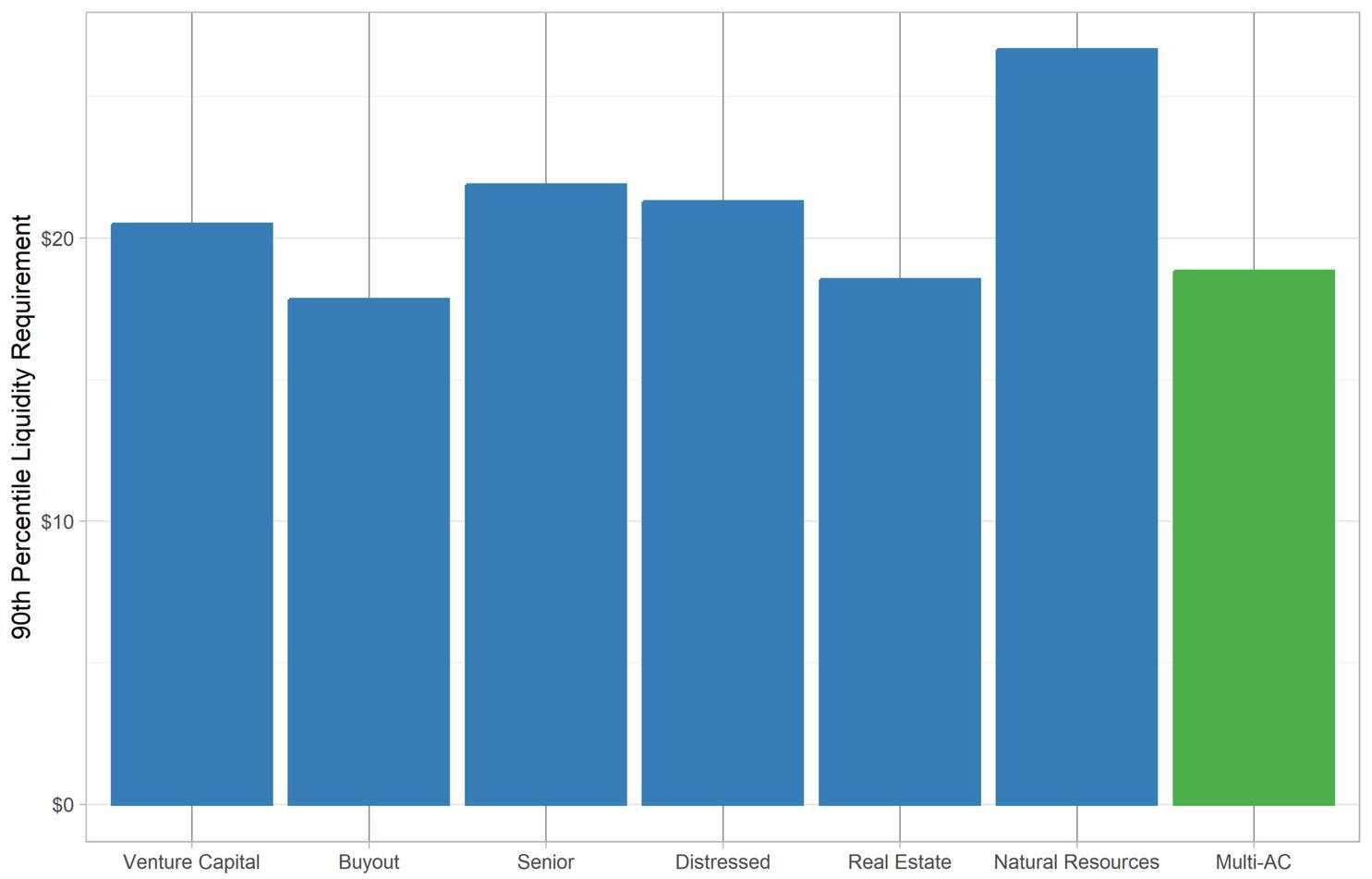

In particular, portfolios that consist of six annual commitments to buyout or real-estate funds require essentially the same precautionary liquidity as our multi-asset-class portfolio, as demonstrated in the exhibit below. The 90th-percentile liquidity requirements, which indicate the amount of liquidity required to meet 90% of all net capital calls, are comparable between these three portfolios. In contrast, the multi-asset-class portfolio requires significantly less liquidity than venture-capital, senior, distressed, or especially natural-resources portfolios, even though two-thirds of the multi-asset-class portfolio is committed to these four asset classes. Diversifying across asset classes appears to reduce the need for precautionary liquidity relative to several different asset-class portfolios. This is likely to be even more apparent when considering tail risks that are more extreme than the 90th percentile.

Diversification across asset classes generally lowered liquidity needs

Each bar indicates how much cash an LP would need to have available in order to meet 90% of quarterly net capital calls (capital calls minus distributions) based on the portfolios in the exhibit above. Calculations are based on the entire period graphed: 2010 through 2022.

Reducing liquidity risk and cash drag

Holding cash-like assets to meet future private market capital calls can come at a high opportunity cost, making liquidity management one of the central concerns for private-asset investors. As such, constructing a portfolio that reduces the need for precautionary liquidity has the potential to improve total portfolio returns. While diversification is primarily treated as a way to reduce return risk, we have demonstrated that diversifying across funds also plays an important role in reducing cash-flow uncertainty. At the margin, diversifying across asset classes provides additional protection against large net capital calls, especially when compared to portfolios consisting of debt or real-asset funds. The cash-flow benefits of diversification — reducing dispersion and volatility — are key to managing liquidity and reducing cash drag.

The authors thank Dan Hadley for his contributions to this blog post. This blog post originally appeared on Burgiss.com. MSCI acquired The Burgiss Group, LLC in October 2023.

Subscribe todayto have insights delivered to your inbox.

1 Our approach is also closely related to the Burgiss Cash Flows at Risk and Pooled Ranking methodologies.2 The Burgiss Private Capital Classification System uses a multitier asset-class taxonomy, where, for example, venture capital is an asset class nested under equity. Throughout this blog post, we use “asset class” to refer to what are also known as “strategies.”3 Idiosyncratic risk is specific to a particular fund and, as such, can be diversified away by committing to multiple funds.4 Furthermore, across all six asset classes, we see noticeable cash flow J-curves. Even in Senior Debt, the asset class with the earliest distributions, you could expect to spend several years contributing capital before seeing a single cash flow-neutral quarter.5 “Market” weights, as determined by fund capitalizations, would not be equal across asset classes; our multi-asset-class portfolio is an extreme version of an asset-class-diversified portfolio.

The content of this page is for informational purposes only and is intended for institutional professionals with the analytical resources and tools necessary to interpret any performance information. Nothing herein is intended to recommend any product, tool or service. For all references to laws, rules or regulations, please note that the information is provided “as is” and does not constitute legal advice or any binding interpretation. Any approach to comply with regulatory or policy initiatives should be discussed with your own legal counsel and/or the relevant competent authority, as needed.