Global cities header

Sidebar Navigation

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Performance Characteristics

- Risk Characteristics

- Aggregating Gateway City Returns

- How do we define a city?

- Conclusion

Amit Nihalani author - research paper

Amit Nihalani

Real Estate Research

GLOBAL GATEWAY CITIES: THE PERFORMANCE BEHIND THE HYPE

GLOBAL GATEWAY CITIES: THE PERFORMANCE BEHIND THE HYPE

-

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

-

INTRODUCTION

-

PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

-

RISK CHARACTERISTICS

-

AGGREGATING GATEWAY CITY RETURNS

-

HOW DO WE DEFINE A CITY?

-

CONCLUSION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

-

Listen to our 7 minute podcast above of an interview with MSCI's Matt Moscardi, Executive Director, Research and Will Robson, Executive Director and Head of Real Estate Applied Research.

Since the Global Financial Crisis, real estate investors have turned to Global Gateway Cities as a key way to diversify portfolios and to generate capital growth. The conventional wisdom asserts these large, well connected and economically dynamic cities should provide more liquidity and more stable cash flows than those available from secondary markets. But have these cities, which include London, New York and Tokyo, offered the superior and safer investments to justify their premium pricing?Our analysis found the office sector in Global Gateway Cities did not provide superior unadjusted returns over the decade ending 2016, based on annualized total returns. Dissecting returns between capital growth and income, we found Global Gateway Cities in general provided higher capital growth, but lower income returns than Regional Gateway and Nationally Significant Cities.

However, we saw a different picture when we adjusted returns for country effects, as national dynamics, including interest rates and general economic conditions, are significant performance drivers. By adjusting for country market averages, Global Gateway Cities were concentrated in the top half of performers. They also displayed higher volatility than their national averages, which was not surprising as these markets are more reliant on capital growth. In contrast, smaller cities generally provided more stable returns with lower capital growth.

Focusing on London, where a wealth of detailed data is available, we found little support for the perceived wisdom that Global Gateway cities have more secure and durable income streams than other classes of cities.

Both country- and city-level trends are important inputs when formulating strategy. Globally consistent data and the flexibility to adjust analysis can help investors better segment geographic areas and improve their understanding of underlying performance drivers.

INTRODUCTION

-

Since the Global Financial Crisis, Global Gateway Cities have been touted as offering better risk-adjusted returns, more liquid markets and enhanced diversification. These cities tend to be larger with more dynamic economies, higher barriers to entry and attractive demographic trends. As such, investors generally expect higher investment returns from properties in these locations and more stable, predictable cash flows. To test whether Global Gateway Cities are in fact “superior” or “safer” than other cities, we evaluated performance and risk across various cities globally.

There is no universally accepted definition of Global Gateway Cities or other city segmentations. For the purposes of our analysis, we defined the following hierarchy of city markets internationally:

- Global Gateway Cities: A small number of large, globally significant and highly connected cities. Typically, these cities are large financial centers and examples include London, New York, Paris and Tokyo.

- Regional Gateway Cities: The next tier of markets comprises cities that are generally smaller and have a regional rather than global significance. This segment includes examples such as Los Angeles and San Francisco in the U.S., with capitals and/or financial centers of major economies in Europe (e.g., Amsterdam and Milan) and the Asia-Pacific (“APAC”) region (e.g., Seoul and Sydney).

- Nationally Significant Cities. These markets are important at a national level. They are usually the main cities of small national markets or economies. Many capital cities of small European economies fall into this category, as do capitals of small or emerging markets in APAC.

- “Other” Cities. This segment consists of all the remaining cities in MSCI’s standard global Index database included in Global Intel PLUS. They tend to be smaller and more secondary markets.

Consistent definitions and data help provide a coherent and cogent analysis. In addition, the global consistency of MSCI’s real estate data and the functionality of its analytics portal allow this analysis to be easily reproduced with modified city definitions.

PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

-

To see how Global Gateway Cities performed versus other international cities, we analyzed metrics such as total return, income return and capital growth. Our analysis covered a 10-year period (January 2007 – December 2016) and focused on the office sector (excluding new development), to control for any differences in sector weightings across markets. The selected period spans a full real estate cycle from peak to trough while covering a very wide sample of cities. Our sample included only those cities for which we have a full 10 years of performance data.

EXHIBIT 1: GLOBAL GATEWAY CITY RETURNS FAILED TO STAND OUT FROM THE PACK

10-YR ANNUALIZED TOTAL RETURN RANKING – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-16)First, we examined annualized total returns for standing office investments across all types of cities, for the period analyzed. No clear pattern emerged, regardless of city classification; cities from each segment were spread across the distribution (Exhibit 1). Global Gateway cities clearly were not stand-out performers in terms of total return during our sample period, contradicting initial expectations.

Exhibit 2: Diversity of Performance Across City Types

10-YR ANNUALIZED RETURNS: INCOME VS CAPITAL – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-2016)Scrutinizing returns by income and capital return uncovered a somewhat clearer pattern: Global Gateway Cities tended to be low yielding, but produced higher capital growth. Exhibit 2 shows that Global Gateway Cities in general provided higher capital growth, but lower income returns (red dots) versus Regional Gateway and Nationally Significant Cities, which were more widely distributed across the chart. The latter showed wide variation in income return and capital growth, spreading across the chart from top left to bottom right.

Adjusting for Country Effects

The interest-rate environment and broad capital market conditions can have significant impacts on variations in real estate total returns. These market dynamics play out nationally as opposed to at a city level; therefore, controlling for this sort of country effect can yield clearer insights. Next, we adjusted city returns by national office market averages, seeking to isolate city returns from country effects.

Exhibit 3: Gateway Cities Relative Performance Improved When Adjusted by Country

10-YR ANNUALIZED TOTAL RETURN (CITY MINUS COUNTRY) RANKING – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-2016)Removing the country effect, Global and Regional markets were clustered in the top half of the distribution (left side of Exhibit 3), with only a handful appearing in the bottom half (right side). A large number of markets were concentrated at the center of the distribution, comprising a large share of their total national market weighting. Not surprisingly, many “Other” markets shifted to the bottom half, illustrating the flip-side of the finding that major cities outperformed their national market averages.

Exhibit 4: Gateways: Low Income/High Growth vs. National Averages

10-YR ANNUALIZED RETURNS: INCOME VS CAPITAL (CITY MINUS COUNTRY) – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-2016)Exhibit 4 shows the effect of adjusting income and capital returns by national office sector averages. By netting out country returns, both Global and Regional Gateway Cities were grouped more tightly at the top left of the chart, with Chicago and Osaka being the only exceptions. Relative to their national markets, these cities tended to have lower yields, but outperformed on a capital growth basis.

In contrast, the majority of the Nationally Significant markets were clustered around zero on both axes as they comprised a substantial percentage of their respective national market on a capital-weighted basis. Elsewhere, “Other” markets tended to underperform on capital growth but provided more attractive income returns. These cities displayed substantially more variation in performance versus their national markets than did Global and Regional Gateway Cities, for both income return and capital growth.

Performance Summary

In short, Global or Regional Gateway Cities did not display superior performance over the last 10 years when compared to global averages. Only by measuring various cities’ performance relative to their national market averages did we see a clearer pattern of outperformance from Gateway City markets. Within countries, these markets tended to outperform competing domestic locations.Even so, there were still some secondary markets occupying the top end of the performance distribution. While their performance drivers may have differed from their Global and Regional Gateway market rivals, they should not be overlooked as potential investment opportunities.

RISK CHARACTERISTICS

-

We now turn to risk, as measured by the standard deviation of returns. City total return volatilities showed a fairly even distribution, with Global and Regional Gateways Cities spread across the spectrum.

Exhibit 5: Country Effect Dominated City Volatility

10-YR TOTAL RETURN STANDARD DEVIATION RANKING – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-2016)

However, a closer look once again reveals a strong country effect, with the U.K., U.S. and Irish markets dominating the top half of the distribution, as shown in Exhibit 5. These markets experienced the harshest downturns in capital values following the financial crisis, but also saw the most rapid recoveries, producing higher volatility as a result. Swiss and German cities dominated the bottom of the distribution, perhaps reflecting the more conservative valuation regimes operating in those markets, which may have dampened volatility.

Exhibit 6: Gateway Cities Tended to be More Volatile Than Domestic Peers

10-YR TOTAL RETURN STANDARD DEVIATION (CITY MINUS COUNTRY) RANKING – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTS (2007-2016)When we adjusted for country effects, nearly all major markets ranked in the top half of the distribution with higher volatility than their national averages (Exhibit 6). This result was not surprising, as these markets are more reliant on capital growth, the more volatile component of total returns.

In contrast, most “Other” cities were found largely in the bottom half of the distribution. Despite this, there were also a significant number of “Other” markets at the top end of the country-adjusted distribution, including commodity-driven markets such as Houston, Calgary and Perth. These cities experienced volatile market conditions in-line with turbulent commodity prices.

Although return volatility can be an important consideration for some investors, it may be less relevant for others. For those with a long-term perspective, viewing real estate as a long duration illiquid asset class and portfolio diversifier, it may not be as relevant. Despite higher mark-to-market volatility for Gateway Cities, some investors may expect a lower level of risk on income streams and from obsolescence in these markets. In larger and more connected Gateway markets, investors may expect cash flows from operations to be more secure, predictable and stable, as there is likely a deeper and broader tenant base from which to select. Similarly, lease covenants are expected to be stronger in these markets.

London and its Submarkets

Are these expectations borne out by the data? The following examples focus on office markets in the U.K., where the widest range of tenancy and lease data is available. They compare London and its submarkets – an archetypal example of a Global Gateway City – versus “Other” U.K. markets.

Exhibit 7: Is the (Lower) Income Return more Durable?

UK LEASE EVENTS REVIEW NOVEMBER 2017 – OFFICE SECTOR ANALYSISExhibit 7, showing office sector data from the most recent UK Lease Events Review,1 analyzes trends affecting new leases in London (blue) and other U.K. regions (gray). There are some surprising findings:

- New lease lengths – New leases in London were shorter in duration than those in the rest of the U.K., potentially offering less income security to landlords than regional properties.

- Break clauses – The percentage of new leases that include break clauses was higher in London than elsewhere in the U.K. London tenants appear to be looking for more flexibility than those in regional markets.

The UK Lease Events Review also provides insights on trends for existing leases:- Outcome of lease breaks – Overall, little difference is evident between London and U.K. regional markets. Although large financial service tenants in the City of London may offer high income security, occupiers in London’s West End are more likely to break their leases than those in the rest of the South East and the rest of the U.K.

- Outcome of lease expiration – Tenants were least likely to renew their leases in the City of London. Renewal rates were slightly higher in the West End, but were highest in the rest of the South East.

- Lease default rates – There was no evidence that default rates were lower for London than elsewhere in the U.K. In fact, for many years the level of defaults for the City of London had been well above the national average, only dropping to its current level in 2017.

Exhibit 8: London Offers Lower Income but Greater Upside Potential

UK IRIS ANALYSIS: REMAINING LEASE TERM VS GAIN/LOSS TO LEASE – UK ALL PROPERTY (Q2 2017)Size of bubble represents share of contracted rent

Again focusing solely on existing leases, Exhibit 8 plots the remaining lease term – a measure of income duration – against the potential gain or loss in income at the end of the lease, as measured by the level of in-place contracted rent versus the current market rent level. The bubbles show the relative size of each rental market, while their shading indicates the degree of credit risk associated with the contracted tenants. The colors of the bubble border indicate the market classification, either Global Gateway (in blue) or “Other” (gray).This exhibit shows London’s income profile to be stronger than other U.K. cities in several respects. For one thing, remaining lease terms in London are longer than for most other U.K. cities, apart from those in Scotland (Edinburgh and Glasgow). However, London’s main advantage is its reversionary potential, the potential gain or loss in income at the end of the lease. At over 20%, this is far above the U.K. average, and stems from the relatively strong rental growth in this market over the last few years – also a key driver of the capital growth story we identified earlier. Despite these positive characteristics, the credit risk associated with income in London is no lower than for other U.K. markets.

In short, London’s conditions offer little support for the perceived wisdom that Global Gateway cities have more secure and durable income streams than other classes of cities. In fact, it seems that tenants seeking new space here demand shorter and more flexible leases. Meanwhile, for in-place income, there is no evidence tenants are either “stickier” or more creditworthy. It is not clear whether these findings can be generalized across all Global Gateway markets. What is clear, however, is that reality is more complex than conventional wisdom might suggest.

1 https://www.msci.com/www/research-paper/uk-lease-events-review-november/0787670910

AGGREGATING GATEWAY CITY RETURNS

-

While we can zoom in to focus on specific markets, we can also zoom out to look at Global Gateway Cities as a group. While Global Gateway Cities collectively outperformed other city segmentations in the years leading up to the financial crisis, they also declined the most, as shown in Exhibit 10. Their annual returns decelerated in 2007 before turning negative in 2008.

However, Regional Gateways experienced the most severe downturn of the city groupings, after slightly underperforming Global Gateways in the run-up to the crisis. Following the crisis, Regional Gateway markets outperformed other city segmentations. Meanwhile the Nationally Significant markets showed much lower volatility, both on the upside and the downside of the cycle. While these aggregations may mask substantial variation between the constituent cities, they provide the context for considering the relative performance of cities within and across the groups.

Exhibit 9: Gateway City Aggregate Indexes

ANNUAL TOTAL RETURN BY CITY GROUPING – STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTSSource: Global Intel PLUS

HOW DO WE DEFINE A CITY?

-

Different kinds of city data are often aggregated within administrative boundaries (e.g., Greater London) and usually encompass a broad definition of the city including the Central Business District (CBD), as well as the areas surrounding it. For many purposes, these standard definitions may be sufficient, but sometimes either a more focused or a broader analysis could be more appropriate. Combined with the dynamic way cities grow and submarkets evolve, this presents a significant analytical challenge. Understanding how the performance of such markets varies — not only within cities, but also between cities — requires the ability to interrogate market data in a highly granular and flexible way.

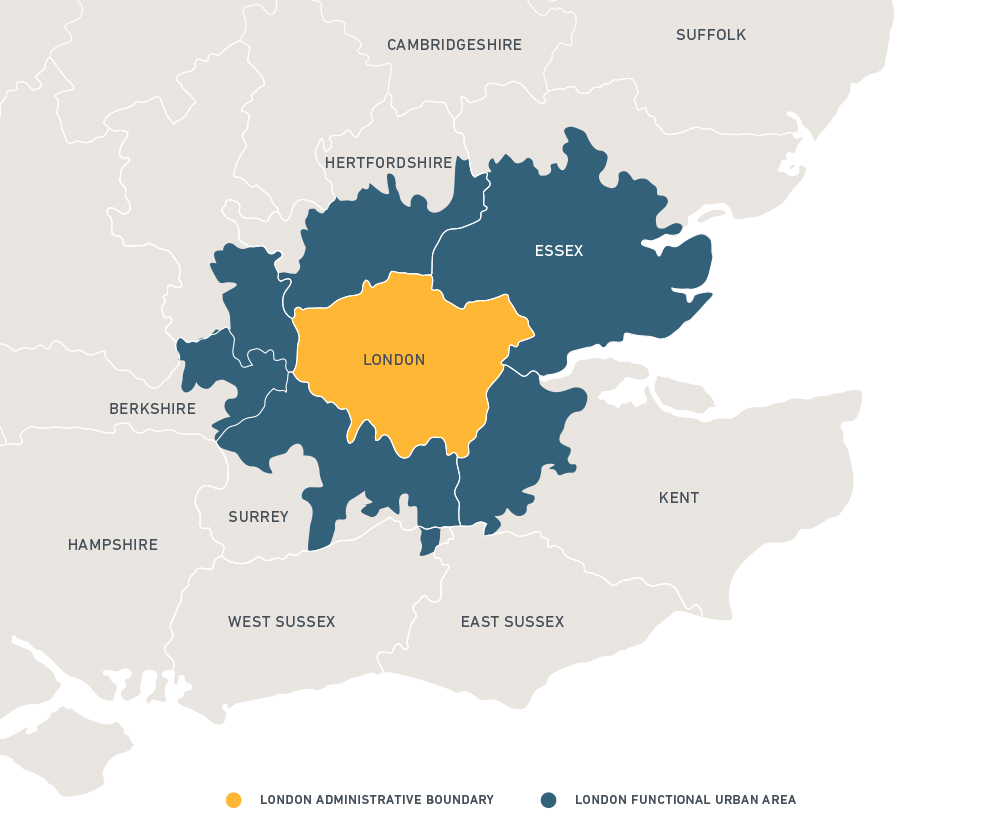

Exhibit 10: What is a City?

Source: OECD

Exhibit 10 illustrates this kind of definitional issue by contrasting the London administrative boundary with the functional urban area of London as defined by the Organisation for Economic Development (OECD). The functional urban area reflects a broad definition of London including the outlying Hinterland and non-contiguous urban areas, whose labor markets are highly integrated with the primary urban core, as defined by commuting patterns.

Exhibit 11: London Office Returns by “Urban-ness”

ANNUAL TOTAL RETURN - STANDING OFFICE INVESTMENTSSource: Global Intel PLUS

In Exhibit 11, we decomposed annual total returns for the various sections of the London office market, using Global Intel PLUS. Merging together the City, West End and Midtown markets to approximate London’s CBD, this segment’s returns clearly correlated strongly with those for the standard definition of Greater London, but provided significantly better returns in the long run. The high level of correlation is not surprising, as the CBD represents a very large part of the overall sample’s capital weight. The Hinterland refers to the secondary market that surrounds the standard administrative boundary of London. While the Hinterland shows a high correlation with the more central London markets, overall it underperformed. A similar decomposition can be applied to other Global Gateway City markets, to better understand variations among submarket returns and their drivers.

CONCLUSION

-

Conventional wisdom suggests large, well connected and economically dynamic Global Gateway Cities should yield superior investment returns. We sought to test this logic by comparing city performance across a number of groupings. While there is no one universally accepted classification scheme for cities, our approach showed the value of using custom segmentations to help understand the relative performance of different types of cities and markets.

According to MSCI data, Global Gateway Cities did not consistently represent “superior” or “safer” investment locations over the analysis period, but they did tend to outperform their national markets, albeit with greater volatility. While city level trends are important to consider, it is clear that national level dynamics were also significant drivers of performance variations.

In general, the ability to define custom market segmentations and apply these in a flexible way to a consistent global database can allow investors to uncover key strategic insights. This analysis requires a more granular and more flexible approach, such as that offered by Global Intel PLUS, to segment areas so that nuances in market trends can be revealed. This way, we can offer new insights into the performance characteristics of larger metro areas.