No time for complacency

Andy Sparks, Managing Director and Head of Portfolio Management Research

Read moremain-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

main-menu-texts.default-featured-content-label

Andy Sparks, Managing Director and Head of Portfolio Management Research

Read more

Chin Ping Chia, Head of Equity Solutions Research, Asia Pacific

Read more

Sebastien Lieblich, Managing Director and Global Head of Equity Solutions Research

Read more

Peter Shepard, Head of Fixed Income, Multi-Asset Class and Real Estate Research

Read moreThe global financial crisis of 2008 fundamentally changed global markets. Its impact on investors cannot be overstated. Here we share reflections from leading MSCI researchers discussing what we learned about risk and markets and where they see the investment world heading over the next 10 years.

AN INTERACTIVE TIMELINE OF THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS

Click through for a brief history of the crisis, from early warning signs in 2007 to the market bottom in 2009.

HSBC says U.S. subprime mortgage losses worsen

Freddie Mac stops buying most risky subprime loans

New Century Financial files for bankruptcy

Bear Stearns liquidates 2 hedge funds backed by subprime mortgage loans

Week-long quant liquidity crunch begins

American Home Mortgage Investment files for bankruptcy

Fitch cuts Countrywide Financial's rating

U.S. Fed cuts bank lending rate by 0.5%

Sachsen Landesbank rescued by Baden-Wuerttemberg Landesbank

U.K. government stops run on Northern Rock

Bank of America buys Countrywide Financial

Scottish Equitable says withdrawals can take 12 months

U.K. nationalizes Northern Rock

HSBC declares $17.2 billion credit crisis loss

JPMorgan Chase buys Bear Stearns with Fed's $30 billion guarantee

U.S. seizes IndyMac Federal Bank

U.S. takes over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

Lehman Brothers files for bankruptcy, Bank of America buys Merrill Lynch

U.S. bails out AIG for nearly 80% ownership, Asian markets plummet

Treasury creates temporary backstop for money market funds

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley become bank holding companies

Washington Mutual Bank sold to JPMorgan Chase, Ireland in recession

U.S. Congress passes $700 billion bailout, Wells Fargo buys Wachovia

Iceland nationalizes its three largest banks

Global central banks coordinate actions

WestLB taps German rescue package

$586 billion stimulus package in China

U.K. takes 58% stake in Royal Bank of Scotland

U.S. rescues Citigroup

Big 3 automakers bailout

Second bank rescue plan in U.K.

$787 billion stimulus package in U.S.

A tectonic shift in risk appreciation - Peter Zangari

The losses and lessons that marked the 2008 financial crisis have touched virtually every corner of financial services. Peter Zangari says the crisis fundamentally affects how many institutional investors think about risk. No longer an afterthought, risk management now plays a central role in the investment process, driving decisions that are defensive as well as offensive.

When did it become clear to you that a global risk event was unfolding?

I don't think of the crisis as a single moment. It was a series of crises that occurred over time. One of the initial signs came to light in 2007 with many quantitative equity strategies suffering severe losses. It’s been reported that these losses were indirectly connected to stresses in the subprime mortgage market. Then it escalated and major banks, such as Bear Stearns, Wachovia and, of course, Lehman Brothers were either taken over or filed for bankruptcy. There was concern about whether other major firms would survive, and about the stability of the U.S. financial system as a whole. People asked: Where’s the bottom? It was a period of time when it wasn’t clear where it would end.

What was a key lesson learned during the crisis?

To me, it’s the awareness and the appreciation of a crisis and the impact it can have on the financial system and across our client base. That is something I see as a significant change since 2008. It’s also one of the most important ideas I try to convey to colleagues who may not have experienced it firsthand.

Are there any other lessons investors should take away from that time?

One of the key lessons that came out of the crisis is the appreciation of how leverage can affect your willingness to take risk, as well as an appreciation of the potential contagion effect across different assets and asset classes.

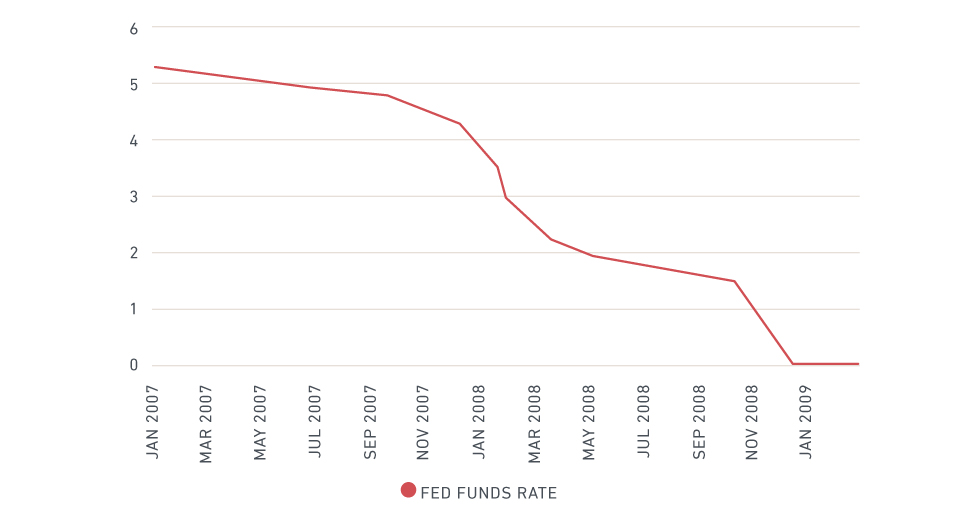

Also, there was a lot of concern about investing in the U.S. public equity markets because of their poor performance. Of course, looking back over the last decade, the stock market has had a terrific run. It was helped, in part, by Fed [the U.S. Federal Reserve] actions, such as keeping short-term interest rates low to encourage investment and economic growth. The market’s performance the last 10 years is an interesting part of the story for investors to remember.

How are investors better positioned today?

For many, the whole culture of risk management in organizations has changed. It used to be a mid-office function, almost thought of as a nuisance. Now one of the top jobs that firms are recruiting for is chief risk officer, and it’s a position that has a seat on management committees and works as part of senior investment teams.

There is also a new way of thinking: Risk management is not simply about avoiding risk or trying to predict the future. It's about understanding your exposures and your positions – and seeing the potential implications of market events. It's also about having the processes and the systems in place to react and to respond appropriately. This way you’re truly managing risk to maximize value. Often, it isn't a question of what you should do anymore, but, rather, what you can do.

What about the next 10 years? What will risk management look like on the 20th anniversary of the crisis?

Looking out over the long run, I can imagine a time when a portfolio or risk manager could call up a digital assistant and ask, “What exposures should I be concerned about in Asia?” This could trigger the analytics, such as what MSCI provides, to look across a portfolio and get managers the information they need.

We've only begun to scratch the surface when it comes to technology's ability to help investors identify opportunities and make more informed decisions, not just at the portfolio level but across an entire organization.

Sebastian Lieblich has two distinct recollections of the financial crisis. On the one hand, he views it as the ultimate test of the validity of the live indexes his team creates, maintains and rebalances. On the other, as someone born, raised, educated in Switzerland, and based there during the crisis, Lieblich says a defining moment was seeing a cloud of uncertainty blow in over Swiss banks.

“We may be only at the very beginning, but I truly think that over the next 10 years, we will see more and more [ESG] standardization.”

Sebastien Lieblich, Managing Director and Global Head of Equity Solutions Research

When you think about the financial crisis, what is your most striking memory?

What really comes to mind is the domino effect that we saw throughout the crisis – how one domino started to fall on one side of the world and just knocked down all the others one by one all over the world over time. Even financial institutions that were supposedly very robust and solid were impacted.

How did that play out in Switzerland?

There was a very key moment for the Swiss people that shocked everyone. That was when the two big national banks, Credit Suisse and UBS, started to be impacted. For Swiss people, these two financial institutions are almost sacrosanct. And when UBS had to ask for a bailout from the Swiss Confederation that was when Swiss people realized that their own financial institutions, which had this reputation of being unbreakable, were not that unbreakable after all.

What did the crisis look like from the perspective of someone who specializes in creating and maintaining indexes?

The indexes followed the markets as they were tanking, which is to say they all behaved the way they were supposed to behave. There were no surprises in terms of the product we were delivering to our clients. It was good from that perspective. By that I mean our clients already had enough turmoil going on in the market, at least they didn’t have to worry about the product they were using from MSCI.

Has the role of indexes expanded since the crisis?

Absolutely. But to answer that correctly, we need to go back even further. MSCI's original indexes were built for U.S. institutional investors who were investing outside of the U.S. and didn't have any benchmark to measure the performance of their portfolios. That use case evolved as the same institutions started adopting indexes as a way to create their investment opportunity set, which led us to create investable indexes. Then these institutions came to the realization that if they were already using the indexes as the basis of their investment opportunity set then maybe they could use them to make their strategic asset allocation decisions and mandate implementation for passive products, such as ETFs (exchange-traded funds).

Since the crisis, institutional investors have become more and more sophisticated. They're starting to move away from market benchmarks to strategic ones, such as our factor indexes, and benchmarks that take into consideration ESG (environmental, social and governance) aspects.

What's behind this shift? What’s the benefit they’re seeking?

At the end of the day, what investors are looking for is higher risk-adjusted performance by deviating from the pure market. When we create our ESG indexes, for example, we increase the weight of companies that have exhibited better ESG performance and vice versa. Investors can use this to tilt their portfolios in ways they believe may increase long-term risk-adjusted excess returns.

One criticism of ESG investing is that different investors have different ideas about what constitutes good ESG. Where do you see this trend going?

It's true that, as of today, there is no standard for defining exactly what ESG means. Nevertheless, we see that most investors interested in ESG are looking for minimum standards that can be applied. For example, many do not want to be invested in companies that are involved in controversial weapons, such as land mines, depleted uranium, cluster bombs, etc. On top of that there are global norms being applied, such as those set up by the U.N. Global Compact.

The point being that, across the world, we can see the same questions being asked by the same types of investors. So, we may be only at the very beginning, but I think that over the next 10 years, we will see more and more standardization.

As of 2014, you’ve also worn the hat of MSCI's Global Head of Real Estate Research. Does the existence of this position reflect the growing role of real estate as an investable asset?

Real estate is clearly playing a bigger role in people's portfolios; it's not lumped in with alternatives any more. We've really seen this with large institutional investors, which now have strategic allocations to real estate. Our clients are looking at real estate as a full-blown sector, full-blown asset class, which deserves its own classification.

How might real estate evolve even further over the next 10 years?

Change is happening slowly, but real estate investors are becoming more and more global. Real estate has been very much a local play. Institutional investors in a given country generally invest in real estate of their own region because they know the specifics of the country and the real estate market. The challenge will be for investors to learn to think local as they increase global allocations.

Jorge Mina is hard-pressed to say what was worse: getting an appendectomy at the height of the financial crisis or watching events play out as he recovered from surgery. To be sure, most people felt the pain of the crisis — financially, professionally and emotionally. Yet, Mina prefers to focus on a valuable product of the boom-bust cycle: innovation.

“These cycles overall tend to be beneficial for growth, despite the fact that there is pain." Jorge Mina, Head of Analytics

What were you doing professionally when the crisis unfolded?

I was working on risk management. I was a founding member of RiskMetrics, which we spun off from J.P. Morgan in 1998. We initially focused on helping banks deal with risk management issues, as well as regulation. Then we started working with hedge funds and other asset managers. I joined MSCI in 2010 when it acquired RiskMetrics.

How did the crisis change how the industry thinks about risk?

Before the crisis, risk management was more or less centered around certain measures of risk. One of the lessons learned is the importance of having multiple views of risk. Risk managers are now looking at many indicators, challenging models, focusing a lot more on stress testing and, most importantly, they are not looking at any one point in time, but at changes over time so they can understand patterns. People are also paying a lot more attention to the difference between what assets look like in calm periods versus when things go haywire.

Finally, financial institutions have understood the importance of communication up and down the management chain, as it relates to risk. A lot of focus is now placed on making sure that the incentives are right, that the conflicts of interest are managed. I think there's a much better balance between the need to take risk and the need to control it.

Have we cracked the code on risk and reward?

For better or worse, there's no secret formula. It's more about making sure that that the risk conversation is front and center, and that everyone understands the risk appetite of their organization. These days, most financials institutions have built up their risk function and the number of asset managers without a professional risk function is extremely small.

Are most firms better positioned today to weather a crisis?

Most crises have been related to credit expansion of some sort. The good news is that right now the leverage in the system is a lot lower than it was. The banks have a very strong capital position. Institutional investors are much smarter, so they have better risk management. Regulators are much more focused on systemic risk. So, yes, I believe we're better situated, but that tension between growth and risk will always be there, and that isn't such a bad thing.

Would you elaborate?

These cycles overall tend to be beneficial for growth, despite the fact that there is pain. I don’t mean to dismiss that pain, but I think it's the reality of how we make progress in the world.

Going back to the crisis, the subprime mortgage market was an innovation that on the one hand was a trigger for the crisis, but on the other hand enabled millions of households to become homeowners for the first time. They wouldn't have otherwise been able to do that. Of course, some people were not able to afford their payments subsequently, and it’s positive that regulators have taken steps to try and protect against this happening again. But there were a lot of people who were able to continue to make their payments and build wealth in the process of doing so.

Are there other examples?

Over history you have a lot of these types of boom-and-bust cycles. You can look at the bursting of the dot com bubble in 2000. Of course, the vast majority of these companies weren't going to make it. But all the innovation that happened as a result of that boom increased productivity in the years to come. Ultimately, that was beneficial. Railroads are another example. There was a lot of exuberance at one point with railroad stocks. They crashed, and people lost money, but the infrastructure for the railroads was still there and because of that we were able to progress to the next stage of industrialization. Another example might be blockchain. I don’t know what will happen with bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, but I am sure blockchain as an innovation will end up providing substantial benefits to the financial services industry.

For any of those crises, but getting back to 2008, specifically, should the risk models have sent signals that could have helped avoid the crisis?

Well, there were some analysts and commentators in 2006 pointing to at least a very high probability of recession triggered by a collapse in home prices, as well as warnings about the rapid credit expansion in subprime mortgages. But the reality is the incentives for investors to take risks were extremely high before the crisis. Trying to blame a model, any model, for the crisis is abdicating responsibility for human behavior.

What will risk management look like a decade from now? Will robots be managing risk for us?

The answer is both yes and no. I think a lot of risk management can be automated; not so much interpretation, but the ability, for example, to go through many more scenarios in an automated way. It is not going to replace human judgment, but it should enable us to focus more on the analysis aspect of the job.

Two crises, countless lessons

Two crises, countless lessons

True to its name, the global financial crisis touched every region in the world. Yet, having gone through a major financial crisis in 1997, Asia fared relatively better than most places, says Chin Ping Chia. Meanwhile, one positive trend he sees as stemming from the 2008 crisis is a more long-term approach to investing. That's giving rise to better stewardship practices and more interest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in Asia.

“I think the pace of ESG adoption in Asia is remarkably fast."

Chin Ping Chia, Head of Equity Solutions Research, Asia Pacific

What is your most poignant memory of the global financial crisis?

I was in Hong Kong, and was following the news as it happened globally. One defining moment, I would say, was the collapse of Lehman Brothers. It was significant for me not just because it was largest bank collapse during that time but because I had friends who worked there. So, overnight, they found themselves with no job. And these were people who had been with the bank for 10 or 15 years. It made it very real.

How did that experience compare with the 1997 Asian financial crisis?

During the Asian crisis, I was the director of the Department of Statistics with the Ministry of Trade and Industry of Singapore. My job was related to finance but not in finance. Having experienced the Asian financial crisis in 1997, though, there was a kind of déjà vu when the 2008 crisis came. The difference, of course, was that the ’97 crisis was contained within Asia, more or less. When the 2008 crisis happened, it involved firms with a global presence, and the world was more integrated, generally, than 11 years earlier, so there was a bigger impact.

Were Asian policymakers and investors better positioned for 2008 because of 1997?

For policymakers and investors who were directly impacted by the '97 financial crisis, there was a lasting fear of another crisis coming. That had its negatives, but it also meant they learned to be a lot more prudent in terms of managing common monetary policy and leverage. Financial institutions had also learned important lessons in the '97 crisis that probably helped minimize some of the impact of 2008. This is not to say none of the Asian countries or markets were affected by the global financial crisis. It’s more a matter of degree.

How did either crisis change your own perspective?

Well, I would say if you can live through a financial crisis, it's actually a good thing because you do learn from it. The important thing is to try to look back and understand what happened, because it is really very easy to forget the causes and effects in detail.

Right after, you tend to see a more conservative approach. As time goes on, the caution level goes down and people start to take on more risk. That's why we’ve seen excessive risk tending to accumulate during long periods of market calm and stability.

What are some of the trends you see shaping up for the next 10 years?

There is no crystal ball here. But I always believe that no matter how much experience you have accumulated over years, there are bound to be some places that you don't pay enough attention to. There will be another crisis. We just don't know from where or how it will happen.

On a positive note, I think investors have a stronger focus on taking a long-term perspective. This is true globally and in Asia, where we see a growing interest in environmental, social and governance issues, or ESG.

How is that playing out in Asia?

We have seen a few large asset owners in the region starting to take a firmer stand. They are making sure that they can put in place much more sustainable investment processes. I think the pace of ESG adoption in Asia is remarkably fast. And this is all driven by some of the largest investors in the country, which have hundreds of billions of dollars in assets. At the same time, you have other pretty good supporting factors, like the implementation of stewardship codes that are driving investors to become more active owners. This adds up to what I think are all the right conditions for ESG to be successful in the region.

Of financial models, reality and the bumblebee

Of financial models, reality and the bumblebee

As the financial crisis unfolded, Peter Shepard witnessed reality confronting theory. "There was a mounting series of events that weren't what anyone expected," says Shepard, who holds a Ph.D. in theoretical physics from the University of California, Berkeley. "It defied everything I read in the textbooks." More than a decade later, Peter has led research and development of many models at MSCI, where he instills in his team a healthy skepticism for the limits of their equations: Even the best financial models, he says, cannot fully account for human behavior.

“You don't necessarily get diversification by investing in lots of different investment vehicles.”

Peter Shepard, Head of Fixed Income, Multi-Asset Class and Real Estate Research

From where you sit, what has changed since the crisis?

One big change that we're seeing across the board is the squeeze on traditional active management. Clearly, that's pushing a lot of investors into passive strategies, and into factor investing. At the same time, it's also pushing a lot of investors into private assets which they believe may offer a premium or a better opportunity for skilled managers. And so a lot of conversations that we have with people thinking about private assets go back to the crisis; specifically making sure the lessons about liquidity are front and center. Some very important institutions really got pinched by liquidity during the crisis. The capital calls kept on coming even as the cash flows dried up. It’s important for today’s investors to keep the past in mind.

The crisis certainly challenged the conventional wisdom on asset allocation. Is the 60/40 portfolio still relevant?

Now it's more like 40/40/20 where that 20 is private assets. But there is also recognition that many of these assets, whether private or public, have a lot in common as far as the drivers of returns. You don't necessarily get diversification by investing in lots of different investment vehicles.

That leads us to factor-based allocations. Increasingly, our clients want to make strategic asset allocation decisions based on these underlying drivers of returns — and then they're determining which investment vehicles are the most efficient way of getting those factor exposures.

Has the proliferation of data made investing more science than art?

The short answer is no. If anything, the crisis taught the danger of mistaking finance for science. One contributor to the crisis, in my view, was former physicists taking their equations far too seriously, and thinking that what they found in an equation was the truth. It’s that kind of reductionist view that I think is really dangerous. We need to understand that math and models are important tools, but ultimately we're trying to describe people. And people's behavior is far more complicated than any equation that I'm able to solve.

How do you make sure that you and your team stay grounded in the real world?

One of the most important challenges in my role now is to instill in people a healthy fear of their models. Most of the work we do is based in scientific practices that make sure the models are robust; for example, we have various techniques for backtesting and stress-testing our models. But then we also try to look at problems from many angles and get a more complete picture.

Maybe I sound like my grandfather, but there are a lot of young people in the industry today who weren’t around during the crisis. They may not realize the extent to which the future might not look like the past. So, as a leader, I need to make sure I help them keep that firmly in mind.

What trends will impact your research over the next decade?

I won't claim to know how a lot of trends will play out, but I do think a number will have an impact. Interest rates have been a one-way bet for decades, and so the prospect of a low-return environment for the next decade seems very real. I think that coincides with some demographic changes that will be very challenging as asset owners work to meet their liabilities.

I also think technology is going to have macro effects. For example, what will the effect of technology be if a lot of jobs are automated? Will it be like the invention of the power loom, where it wasn't so great for the weaver but the people who could operate the looms had better lives? Or will it really leave people behind and change the structure of the economy?

What do you think this means for your industry over the next decade?

It's very likely that the role of technology, big data and artificial intelligence will have a large impact in areas where scale is the primary impediment. But for problems that smart people have struggled with for decades, such as, “What is the optimal asset allocation?” I'm not convinced a machine will be able to take that over.

Think about the fact that the most powerful artificial intelligence networks recently surpassed the brain power of a bumblebee, and they're closing in on a tree frog. Bumblebees are very impressive — and that level of intelligence may be enough for, say a self-driving automobile — but I’m not sure I’d ask a bumblebee to manage my mother's retirement income.

Investors tuned into corporate governance trends leading up to the financial crisis might have seen clues of what was to come, says Ric Marshall, chief architect behind MSCI's ESG and corporate governance ratings model. After all, Marshall continues, the composition of a board and the actions it takes, such as setting incentives for senior executives, is a “pivotal point where the interests of investors interface with company management.”

A decade later, there is far greater awareness of the importance of good governance, says Marshall, but “as long as companies are run by human beings, investors will want to be vigilant.”

“As long as companies are run by human beings, investors will want to be vigilant.”

Ric Marshall, Executive Director, ESG Research

When you think back on the financial crisis, what moments stand out?

For me, it started when Countrywide Financial was seriously downgraded in late 2006 and it became clear they were in trouble. We didn’t have any inkling as to how serious it was going to get, but Countrywide was on the leading edge of a lot of what was going on in the mortgage industry, and it was also a company I happened to be following very closely because of concerns around leadership and CEO pay. It was the first real hint that things had the potential to go south.

Another big touchstone for me was General Motors testifying before Congress and asking for help. I had previously suggested in a client presentation that General Motors, despite its size and history, had the potential to go bankrupt. I remember a lot of people tittered and probably thought I was crazy, yet, now, here it was.

What else did you see through the lens of corporate governance?

The most obvious tipoff was the big run up in CEO pay in the U.S. financial sector that occurred in 2006 and 2007. We knew this was a problem, but we certainly didn't know what it portended. There was such a significant shift in pay levels in that sector that it actually skewed our overall ratings. We even thought there might be something wrong with our model. But it turned out our model was working quite well, and simply reacting to something that we had not previously seen.

The other big area was the nature of the boards, namely the lack of appropriate experience and what we call ”over-boarding,” which is when directors sit on so many boards that it threatens their effectiveness on any one of them.

How pervasive was over-boarding?

Between July 2007 and the end of 2008, 17 of the companies that were in the middle of the crisis lost about $1.3 trillion dollars in shareholder value. When I wrote a report shortly afterwards that asked, “Where were the boards?” it became very clear that over-boarding and the lack of appropriate skill sets, were urgent problems at nearly all of those firms. Eleven of those 17 companies had at least one over-boarded director, six had two or more and one had an astonishing five over-boarded directors.

Would better governance have made a difference?

The financial crisis wasn't just about corporate governance, but I believe you could make the case that stronger corporate governance could have prevented it, or, at the very least, lessened its severity. Collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps might have come along anyway, but if boards had been more effective at doing their job, I'd like to think they would have limited the exposure. And even with sub-prime mortgages themselves, more effective boards might have done a better job of limiting the risks involved.

Has the financial crisis changed how investors think about governance?

The financial crisis effectively put exclamation marks around what we had gone through a few years earlier with Enron and Worldcom. Consciousness around the importance of corporate governance has increased. There's been a growing emphasis on board qualifications — boards are more qualified than ever — and also on board diversity. Not just gender diversity but ethnic and racial diversity, and diversity of experience and opinion.

At the same time, here we are 10 years after the financial crisis, and CEO pay levels and share buybacks are just about back to where they were just prior to the crisis. That's not to suggest there's a financial crisis imminent, but merely to point out that we are seeing some of the same signs we missed before.

I recently looked up some of the individuals who were on the boards of those 17 companies I mentioned earlier, and several of them are still serving on one or more U.S. boards. That seems very striking. These individuals were part of a failed system, and yet they are still active directors; still responsible for overseeing key aspects of our capital markets.

What will corporate governance look like in another decade?

I would have to say that many aspects of the corporate world will likely remain the same. Companies are run by human beings, and there will always be companies that get into trouble.

On the other hand, there are trends in motion that are very positive. For one thing, we’re getting more sophisticated in our ability to evaluate concerns and understand the relationships involved in corporate governance. Another is the move toward greater board diversity. Ten years from now an entirely new generation will be serving on corporate boards, bringing with them an entirely new range of life experiences and expectations. That will also make a difference. Hopefully, it will be a positive one.

For many, the financial crisis is a well-worn chapter in market history: a case study on the danger of hubris and power of systematic risk. For Andy Sparks, it’s personal. With responsibility for Lehman Brothers' index group and client portfolio analytics at the time of the crisis, he needed to keep his division afloat even as his employer was barreling toward an uncertain fate. Andy says that experience is invaluable for identifying and simulating events that could have profound effects on clients' portfolios.

When you look back on the financial crisis, what stands out most?

I was at a firm at the center of the explosion, and have vivid memories of going through a bankruptcy while also having to continue to do my job. Despite everything, the show goes on. We needed to make sure our indexes were being published and our client-provided risk systems were operating, because risk management is most needed precisely when there's a chaotic market environment. Those were long days.

What do you bring to the table now because of that experience?

There's the personal dimension — including what I learned as an employee weathering adverse circumstances at a firm. Then there is the market perspective. It provided a wealth of lessons about what went wrong. The crisis and its aftermath continue to affect investment behavior, portfolio management and risk management practices, which is a good thing.

Any specific lessons that stand out?

Diversification is really important. I think one of the most important lessons of the crisis is not to be too greedy, not to get too concentrated in any particular asset classes. And to remember that it's hard to predict the timing and the cause of the next crisis, but that they do occur more frequently than the models say they should.

Today, you help institutional clients understand different scenarios that would affect their portfolios. What are their biggest concerns today?

On the fixed income side, there are concerns about potentially higher inflation, and tightening credit spreads that are close to where they were before the crisis, and there’s a growing amount of corporate leverage brewing beneath the surface. Last but not least, there’s the exit of central banks from quantitative easing.

Investors seem to have a love/hate relationship with quantitative easing. How would a proponent describe it with the benefit of hindsight?

The idea was to try to address a lot of the dislocation caused by the crisis and the failure of multiple financial institutions, including Lehman Brothers. You had the possibility of a sustained recession, and a major downward spiral, particularly for mortgage securities, which performed extremely poorly in the aftermath of the crisis. And don’t forget that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, for-profit companies and dominant players in the mortgage market, were effectively taken over by the U.S. government.

In the face of this, the Federal Reserve almost instantaneously provided price support to the mortgage market, and, before long, spreads were tightening, and that had a very nice ripple effect on major financial institutions. Quantitative easing helped restore order to the markets. In its absence, there might have been further dislocation and the crisis might have been prolonged.

And the skeptics?

I think even skeptics would agree the recession would have been prolonged, but there are some who don't think that quantitative easing did much beyond that; that the positive trends we've seen since would have occurred more or less anyway. They would also say there’s a warning in what they see as central banks financing government treasurys, effectively printing money, buying bonds that governments are issuing.

There's another class of criticism around what used to be called the “Greenspan put.” The idea is that, when you allow the Fed to come in and bail out private sector firms, the market begins to expect that. This line of discussion is that it might have been better to let a few more financial institutions fail, to teach the lesson that in the next crisis firms would need to bail themselves out.

So, what does the future hold? Are you worried about another crisis of that magnitude?

There’s a continued push toward transparency, along with advances in technology that could allow for greater amounts of better, readily accessible data and improved models, and help investors reduce risk. On the other hand, greater transparency could make it more difficult to generate excess returns.

You never know exactly what’s next, though. In early 2007, it was calm waters, blue skies. And then, a year and a half later, all hell had broken loose. So, I think it’s very prudent for all market participants to be a little paranoid. But do I personally think there's some major crisis looming? No. Do I think the market may be a little complacent now because of actions that the Fed and other central banks took in the aftermath of 2008? I'd say yes.

In addition to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s asset purchases that Andy Sparks discusses, they also sought to stimulate growth by bringing the Federal Funds rate down to zero – where it remained until December 2016. Such moves illustrate the enormity of the crisis and the extraordinary measures taken to address it.

George Bonne admits his timing hasn't always been perfect. The Harvard University physical chemistry Ph.D. joined the semiconductor industry near the height of the tech bubble. Then, in 2006, he shifted into finance, where he created novel quantitative models for what is now Thompson Reuters StarMine—just in time for the financial crisis.

“Investors became more aware of the potential for ‘extreme events’ [after the crisis], and the need to diversify across factors, not just across asset classes.”

George Bonne, Executive Director, Equity Core Research

For starters, how would you describe factor investing to, say, your mother?

It's taking the emotion out of the investment decision and buying securities based on some systematic, generally simple rules that have statistically been shown to have generated excess return over long periods of time. That might be, for example, buying securities that are cheap relative to their earnings. Factors are predominantly used in equity investing, but are expanding to other areas, such as fixed income. I hope Mom can understand that.

The truth is, it can be difficult for people to wrap their heads around. Quant folks like me have been using factors for years, but factor investing has only recently become more widely used.

You came to finance from academia. How did you make the leap?

My graduate work was modeling chemical reactions taking place in the atmosphere. Then, when I was in semiconductor equipment engineering, a good chunk of my time was spent modeling the performance of the equipment, trying to predict when it would need to be serviced before it actually broke. Now at MSCI, my team and I build models used in analytics and index products. At first glance my career trajectory might seem meandering, but the common thread has been building models and conducting analysis with large amounts of data. The fundamental skills and techniques required in all of these areas are all very similar.

Did the financial crisis make you second guess that last career move?

Not quite. I certainly got in at a high point for quantitative investing, but I think it has since passed that high water mark. The financial crisis actually served as a positive for factor investing, increasing people’s awareness of factors as drivers of risk and return.

Would you say the financial crisis sparked interest in factor investing?

There is some relationship. Investors became more aware of the potential for “extreme events,” and the need to diversify across factors, not just across asset classes. For example, funds tracking MSCI's Minimum Volatility Indexes increased in assets and popularity after the crisis. I think, more importantly, though, there is that greater recognition of factors as risk and return drivers, and that there are systematic factors that have demonstrated long-term risk premia over time. If you can create a strategy — and at low cost — to capture this, why wouldn't you?

What is the Holy Grail for factor investors?

People are always seeking ways to identify and understand new and uncorrelated information and sources of alpha [excess returns]. The explosion in data science and different types of data has made people scramble to try to be unique in what they do, and not miss out on information their peers may be looking at.

How has factor investing evolved over the last decade?

It started out with the most well-known, well-studied academic factors based on very traditional data — company fundamentals, earnings estimates, pricing. Now you're seeing more variety. For example, we recently built a model for sentiment factors, such as options, short interests and social media.

There are clearly pockets of value in alternative data, and we are looking at them. However, investors need to consider the complete picture. For example, with traditional data you get coverage of about 30,000 companies, but with some alternative data sets you may cover only 30. Also, machine learning algorithms have been around for many years, but recently we’re seeing a lot of hype about using them and AI (artificial intelligence) in the investment process. Using these terms with VCs (venture capitalists) has been a great way to get funding, but I think thus far, the hype mostly has outweighed the value.

What about the next 10 years? Where is factor investing headed?

As people get more comfortable with factors, we’ll see a continuation of the trend toward the “quantification” of investing. Even fundamental managers are realizing they need to somehow incorporate factors and quantitative tools into their investment process. We’re already starting to see specialized indexes based on alternative data, and I think we’ll see more factors and indexes based on them as alternative data becomes more mainstream. We will see factors constructed from non-linear techniques, and those dynamic strategies I mentioned may increase in complexity, and will likely be driven by more complicated algorithms or machine learning as technology advances.

Rethinking what it means to be globally diversified in real estate

Rethinking what it means to be globally diversified in real estate

The financial crisis underscored the importance of taking a more nuanced approach to diversification and risk management. Yet, when it comes to real estate, investors still tend to paint the asset class with a broad brush. Part of the issue, says Will Robson, is accessing and analyzing data that can be translated across global real estate markets, and applied to the total portfolio.

“Real estate has always had a high home bias, and so global diversification is a relatively new thing in real estate compared to say, equities."

Will Robson, Executive Director and Global Head of Real Estate Applied Research

What was happening in real estate at the start of the financial crisis?

The U.K. commercial real estate market had just opened up to daily-priced real estate funds, and there were huge inflows from retail investors. You had these quite liquid investment vehicles for investing directly in real estate, which is in itself an illiquid asset class. Still it was relatively easy to raise capital and everyone wanted in. Then the financial crisis hit, and everything turned negative very quickly.

How would you characterize the market today?

One thing we've seen in the recovery is that investors are much more focused on prime high-quality real estate in high-quality cities and locations. In the heady days of 2005 and 2006, there was a lot more investment volume spread across the whole quality spectrum, and debt was much easier to come by than today.

What other lessons did real estate investors learn?

Pre-financial crisis, people talked about real estate as being a diversifier for a portfolio, but they focused on valuations rather than transaction pricing. This tends to underestimate the volatility and correlations with other asset classes. People thought real estate provided more of a diversification benefit to their portfolios than perhaps it did.

Up until the crisis, I don't think people were really analyzing their real estate exposures in any systematic way as part of a multi-asset portfolio. The fact that real estate was such a big part of the story really highlighted the need to understand the interaction of real estate with other asset classes.

Is that easier to do today than a decade ago?

It's still a work in progress because most real estate-focused investors still are operating in a world where everything is based on their valuations. They think of risk in terms of individual buildings, things like lease agreements and tenant mixes. And that’s hard to get away from. Unlike in equities, where you’re not involved in day-to-day management of the company, per se, with real estate, you’re managing a business plan, as well as a portfolio.

You’re also dealing with a very broad spectrum in terms of risk-return characteristics, ranging from very safe, long-lease properties, all the way to speculative ground-up developments in emerging economies. Today, people are interested in understanding in a bit more detail what kind of real estate they're investing in and identifying the common risk factors. Still, the challenge is finding a way to analyze risk in real estate that speaks the same language as other asset classes.

How about geographically? Are investors more diversified globally?

Real estate has always had a high home bias, and so global diversification is a relatively new thing in real estate compared to say, equities.

You can see the potential for diversification when you just look back at returns around the crisis. You had markets like the U.K., Ireland and the U.S. that had quite a violent response, whereas a lot of European markets had a more delayed and measured response in terms of their real estate valuations. Then, some parts of Asia didn't really have a downturn at all in their commercial real estate market, on a valuation basis at least.

Why have investors been slow to adopt a more global approach?

Real estate is such a local business — even the definition of a yield can vary from one market to another — so having data that is comparable is actually quite a challenge. We’ve worked for the last few years trying to bring as much standardization as possible to the way that real estate returns are measured and the methodologies behind that. We’re trying to build a bridge where there is more information about the specifics of an investor’s portfolio, but also allow them able to consider risk from a macroeconomic perspective.

What trends will change real estate investing over the next decade?

Because such a big part of data analysis in real estate is actually getting the data, cleaning it and making it usable, if technology can advance to facilitate that, maybe that will encourage more people to share data. When more data is available, the analysis becomes more sophisticated. Hopefully, that will allow us to apply similar factors, terminology and analysis techniques from the equities markets to private real estate and have everybody talking a similar language.

As that happens we should see more and more standardization in other areas, such as legal or contractual aspects. Things like blockchain may help make it a more global and liquid market. That could have massive implications, improving real estate's potential for diversification and increasing its role in multi-asset portfolios.

As the world saw during the financial crisis, the nature of securitization – bundling financial assets, such as home loans, and turning them into tradeable securities – makes analyzing these investments extremely complex. David Zhang has dedicated most of his career to helping investors get to the bottom of what they're buying. It's a constant work in progress, he says, given that changes in regulations, risk regimes and borrowers’ behavior, to name a few, can throw a wrench in even the best models.

“The crisis drove home that you cannot look at the data in isolation.”

David Zhang, Head of Securitized Products Research

Where were you when it became clear the housing crisis was becoming a global financial crisis?

I was working at Credit Suisse as head of securitization quantitative research. So I had a front-row seat in the bubble years, the mortgage and financial crises and the subsequent recovery and reforms. The first sign of trouble showed up in the second half of 2007 when the mortgage market experienced a sharp increase in so-called early delinquencies in the private label MBS [mortgage-backed security] market. This was unprecedented, as borrowers hadn’t been delinquent that quickly after loans closed. This revealed serious problems in mortgage underwriting and led to a sharp depreciation of private label MBS. Initially this was an isolated issue, but in the next six to eight months, banks whose assets were tied to these securities and had weak capital and liquidity positions started experiencing severe stress. Remember, the MBS market back then was larger than the Treasury market.

For me, the defining moment of a mortgage crisis becoming the financial crisis was in March 2008, when Bear Stearns was sold to J.P. Morgan, with funding support from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. I remember I was in a Tokyo hotel room, packing to go to the airport when I saw the news that J.P. Morgan was paying $2 per share for Bear Stearns.

How has the industry changed in the last decade?

The reforms of the last decade have touched nearly every aspect of mortgages and securitization in general; there have been changes in accounting rules, disclosure rules and capital and liquidity requirements. They have profoundly changed and improved the mortgage and securitization market. Meanwhile, whole industries have sprung up to increase data and analytics abilities for mortgage investors to look at MBS with much more in-depth analysis.

What are some of the key lessons that came out of the crisis?

Before the crisis, investors, modelers and rating firms relied heavily on data from the bubble years and on assumptions that proved wrong. For example, the mantra was that there never had been a national U.S. housing downturn, and that correlations between the performance of various asset types were low. All these assumptions were held forth as unchallenged truths until the crisis exposed them as inadequate.

Fortunately, investment technology has also advanced significantly post crisis. Big data analytics is one of the most positive trends emerging from that time. Overall, there is a sense that investors need do more and better analysis to “know what they own,” especially in the securitization space. The crisis drove home that you cannot look at the data in isolation.

How are investors better positioned to know what they own?

Post crisis, the industry disclosed a huge amount of new data, especially in mortgage issuance and performance. MSCI was a leader in the research community in terms of using these data to understand the causes of the mortgage crisis and the potential impact of newly proposed government policies. We also suggested new policies and practices. For example, we did a pioneering study that combined mortgage loan data with consumer credit bureau data to gain unique insight on why – contrary to conventional wisdom – borrowers who weren't underwater experienced large default rates. We also researched collateral composition and performance for other securitizations. These include [government] agency backed securities and collateralized loan obligations, both of which have boomed in recent years.

In addition to understanding collateral better, investors have been doing more analysis on the structuring side, relying less on rating agencies.

What are the biggest trends in securitization you see for the next 10 years?

One big trend may be the growth of securitization in Asia. In the next five to 10 years, the Asian securitization market may rival the U.S. market. Since the crisis, many Asian countries have been keen to learn the lessons that came out of the U.S. crisis so they can avoid a similar fate.

Big data and artificial intelligence (AI), meanwhile, should be very important in terms of investment and risk management. These could lead to profound changes in how we research investments, how we build risk analytics and for overall operations.

How can AI improve securitization research?

One issue with analyzing securitized products is the large amount of data required and the large amount of risk factors. AI can give you a much better, more efficient way to deal with the kind of data we're analyzing and find new ways to analyze risk, such as linking public securities data with consumer data, and with other non-traditional data.

As the financial crisis progressed, Laura Nishikawa was working for a small research firm, where she focused on environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices of banks and consumer finance companies. Suddenly, information that had seemed “nice to have" became critical.

“I think some of the resistance [to ESG] is actually more emotional than empirical.”

Laura Nishikawa, Executive Director and ESG Research Director

What were some of the red flags for you that a crisis was brewing?

We were focused on looking for nontraditional financial indicators that could help us assess, for example, a bank's exposure to those types of risks. And at the time that was hard to do because the information wasn't widely available. What was really remarkable, though, is we often found the banks themselves didn't have a clear picture of their exposure. Even if they did, there was a reluctance to look at things outside of how they had historically behaved.

Where were you when things came to a head?

On Sept. 15, I was at a sustainable banking conference, and even though Bear Sterns and other prominent firms had run into trouble, nobody was talking about a lot of the bigger systemic issues. There was still a tendency to look at these different pieces in isolation. Then all of a sudden everyone's phones start going off as word got out that Lehman Brothers was filing for bankruptcy.

How did the crisis help or hurt research on ESG issues?

In 2008, a lot of our little ESG firm’s clients were suffering — some ceased to exist. We had a lot of “is this the end of ESG?” discussions.

In the end, there were a couple of areas, such as carbon markets, that were hurt. But the crisis was actually the most important catalyst in bringing ESG from a niche consideration to a much wider audience. We saw some larger, more sophisticated investors start to think more critically about how this additional information could help them make better decisions and understand some of the blind spots in their risk management systems.

You still hear people say ESG investing can limit returns. What would you say to that?

I think some of the resistance is actually more emotional than empirical. We've done a lot of research on the question of ESG and performance. When we look at a stock-specific level, there is empirical evidence that ESG considerations have been related to profitability, to tail risk, to systemic risk and devaluation. Meanwhile, changes in ESG — companies getting better or worse on these criteria — have been a fairly significant performance signal.

Your team helped create a family of ESG fixed-income indexes. Are more fixed-income investors incorporating ESG into their analysis?

It's still early days, but fixed-income adoption of ESG is one of the biggest growth areas with a lot of the focus on corporate bonds, and credit in particular.

There’s quite a lot of evidence that governance factors are significant from a credit risk perspective. For example, while corporate defaults may not be solely the result of governance failures, they have usually played a role. Whether it’s fraud or misrepresentation, or something less egregious, such as strategic failings, we’ve seen that governance may provide a forward-looking credit-risk signal.

If the last decade has been resurgent for ESG, where will we be 10 years from now?

People love to say that ESG won't exist in 10 years because it'll just be part of investing. But there’s a utility to focusing on emerging risks that aren't widely accepted or known, and to do so with data that are spotty and more challenging.

So, I do think ESG increasingly will be incorporated into security selection and investment mandates and asset allocation at a higher level, but that it we will still see it as a distinct practice.

We're also going to see increasing use of new technologies and alternative data sources to get a better picture of how these factors can affect investment performance. Perhaps using some of this data, such as from satellite imagery, to better understand company's environmental exposures at a more granular asset level.

We've talked about the practical benefits of ESG research, but what about the broader impact?

One of the really big lessons of the financial crisis was how ESG issues can be significant to companies. I don't think a lot of people realized how dislocations and weaknesses in one sector could spill over to the economy and society as a whole.

The crisis taught us that your investments are only as strong as the system in which they operate.

The phrase “global financial crisis” is no exaggeration: It impacted markets around the world and touched virtually every asset class. Yet, as Dimitris Melas observes, the widely held notion that investors had nowhere to hide is not entirely correct. On the contrary, the crisis underscores the importance of diversification, says Melas, and is a prime example of how catastrophe can make way for opportunity.

Looking back, what do you consider the height of the crisis?

Without a doubt, it was mid-September of 2008, specifically the weekend over which Lehman Brothers collapsed. I was already working for MSCI at the time and, as I am now, was based in London. Up until that point many of us in investment management and financial services felt that the crisis had been about liquidity, specifically in the banking sector, and triggered by a fall in property prices. But over that weekend we realized that had changed. It was about solvency; the solvency of some pretty major financial institutions.

How did that experience compare with other turns in the market?

The two bear markets I have experienced in my career have been quite different, both in terms of what caused them and also the time period over which they unfolded. The problem during the 2000 to 2002 bear market was excessive valuations for technology companies, and equity markets in general. The bear market that followed was relatively protracted; the stock market fell by 10% to 15% every year for each of those three years.

This is quite distinct and different from the global financial crisis, where equity valuations never became excessive. What happened is that fundamentals, especially for the financial services sector, collapsed and that led to the problems that followed. During the financial crisis equity markets fell fast and sharp, but it lasted only a few months.

Were there any similarities?

In both cases, if you were brave enough and had the foresight to actually increase your exposure to equities and other asset classes, you would have earned very good returns over the subsequent five or 10 years.

Did diversification provide any protection?

Absolutely. One of the myths you'll often hear is that when you have a crisis, like the one we had in 2008, selling is indiscriminate, and everything goes down. Actually, if you look at what happened in 2008, government bonds, gold and the U.S. dollar are examples of areas that rallied during the crisis. Regionally, there were differences as well. Within equities, of course, nearly everything declined in 2008, but in relative terms, some sectors, such as utilities and consumer staples, which tend to be resilient through the market cycle, and certain strategies did much better than others.

Any strategies specifically?

For equity investors, low volatility strategies, time and time again, offered relative protection to investors. For many, it makes a huge difference to lose 20% of the value of your portfolio, versus 40%.

You have a Ph.D. in Applied Probability. Did the crisis confirm or contradict anything you learned in your studies?

Even before the crisis, my experience working in financial services taught me to be much more practical and not rely exclusively on models or theories. They can be very attractive and elegant, and can describe the world most of the time, but during extreme market conditions some of their assumptions don't hold up.

The financial crisis may be the most extreme example, but there are smaller episodes that are very interesting and worth studying. If you look at the 10 years since the global financial crisis, we have had everything from the eurozone crisis to the sudden return of volatility in early 2018. Again, one of the things you see time and again is the importance of diversification.

The last decade also has given rise to big data, advanced analytics and other technology. What are the implications for investors now and over the next 10 years?

Technology is playing an increasingly important role in the way investors assess markets and evaluate opportunities. One example that we see happening today is how quickly, through social media and other relatively new ways of communicating, news spreads about companies, especially when they have a negative event. That can damage the reputation of companies and that can be reflected in the share price much faster than before.

On the other hand, improvements in ESG (environmental, social and governance) research have helped highlight underlying problems earlier, before companies actually experience those negative events. So you have the bad and the good.

Another place where technology has helped us do our jobs is in our equity factor models. We used to rely almost exclusively on market or accounting data, but now we are able to add other factors, including news sentiment, which relies partially on information from social media and other non-traditional sources.

Keep in mind, however, that disruptive innovation is not something new. Even if you go back 20, 30, 40 years, the development of indexes and risk models was tremendously disruptive. And that led to a huge explosion in different types of instruments, including index funds and exchange-traded funds that have really democratized the investment process.

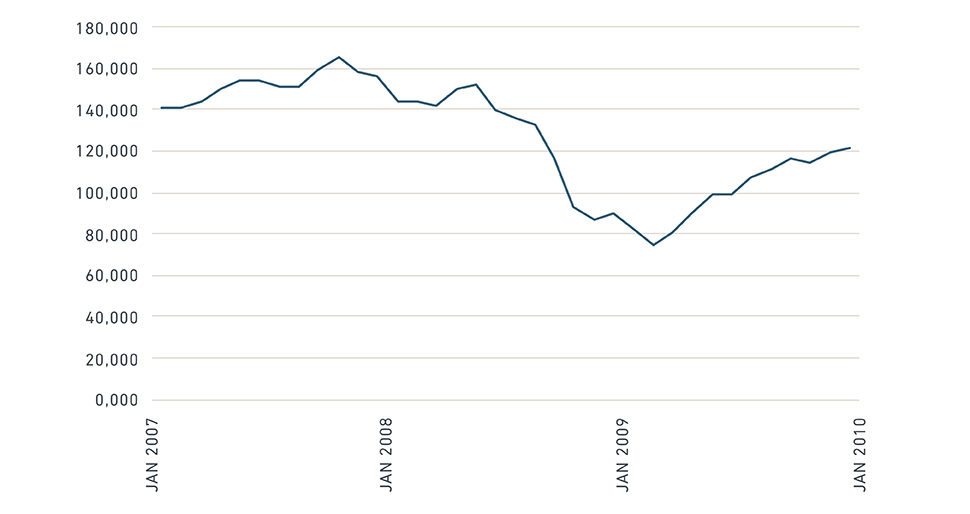

While equity investors had almost nowhere to hide in 2008, Dimitris Melas explains that “equity markets [illustrated by the MSCI ACWI below] fell fast and sharp, but it lasted only a few months.” This was in sharp contrast to the three-year bear market following the dot-com bust in 2000.